The Lilongwe Society For the protection & care of Animals

Located in the south-east of Africa is the landlocked country of Malawi. The majority of its estimated population of 14 million still live in a rural environment and with an economy still heavily based on agriculture, it is among the world’s least developed countries. The country has a low life expectancy, infant mortality is high and there is a growing HIV-Aids problem. However, the country is democratic and relatively stable, meaning that healthcare, education and environmental conditions have all recently improved, and the country has started to move away from its reliance on overseas aid.

Malawi is often described as the ‘warm heart of Africa’ or ‘Africa for beginners’ and for myself, this is very appropriate, as this is my first sojourn to the continent. My purpose is to photograph and document the work of the Lilongwe Society for the Protection and Care of Animals (LSPCA), the only charity in the country working to improve its standards of animal welfare.

I arrive mid-afternoon at the modest Lilongwe International Airport to be greeted by a plethora of placards, almost all bearing the names or logos of global aid organisations. Eventually I locate mine and I am soon speeding towards a capital of 1 million people in a ramshackle taxi, which has probably just as many stories to tell as its driver.

After checking in at my accommodation I grab my kit and walk the short distance along wide roads to the LSPCA veterinary clinic, located in a residential area of the city of relative low density and tranquillity. The LSPCA was established in 2008 by a determined and dedicated group of Malawian residents with crucial support and funding from RSPCA International. Its aims were, and still are, to improve the welfare of domestic and farm animals across this small African country where animals play such an integral role in the everyday lives of its people. It does this by providing veterinary care from its fixed and mobile clinics, by establishing an extensive education programme in the city’s schools and by working closely within local communities to combat rabies and Newcastle disease, the latter being prevalent in chickens. The LSPCA has also developed strong partnerships with the government who strongly support their work.

I am met at the clinic by Dr Richard Ssuna, the LSPCA’s Project Manager and Chief Veterinary Surgeon and by Donnamarie O’Connell, who is the RSPCA International’s Senior Programmes Manager for Africa. I hand over a small suitcase that is crammed full of medical supplies, which is gratefully received. I’m then given a quick tour of the newly acquired building and am immediately struck at its sparseness and lack of basic amenities. In the room that serves as an operating theatre, a cat lies under a battered heating lamp, recovering from an operation. It’s a small taste of what is to come. Dusk turns swiftly to night as darkness cloaks the capital. I return to my hotel, and during unpredictable power cuts, prepare for the days ahead.

Monday morning is dry and hot. Its half past eight and I’m bouncing around in the back of a pick-up truck on my way to the Lilongwe Demonstration School to watch the LSPCA’s education programme in action. My driver, Joseph Kwanunkhatonde, is a young, smart and positive individual who on the surface appears slightly reserved. He is also the LSPCA’s Education Officer and he is returning to where he was once a pupil. The establishment is large, with over 1,700 students ranging from 6 to 15 years of age. As we walk towards the headmaster’s office to formally announce our arrival, our pick-up is engulfed by an army of small children, who excitedly transform it into a metallic trampoline.

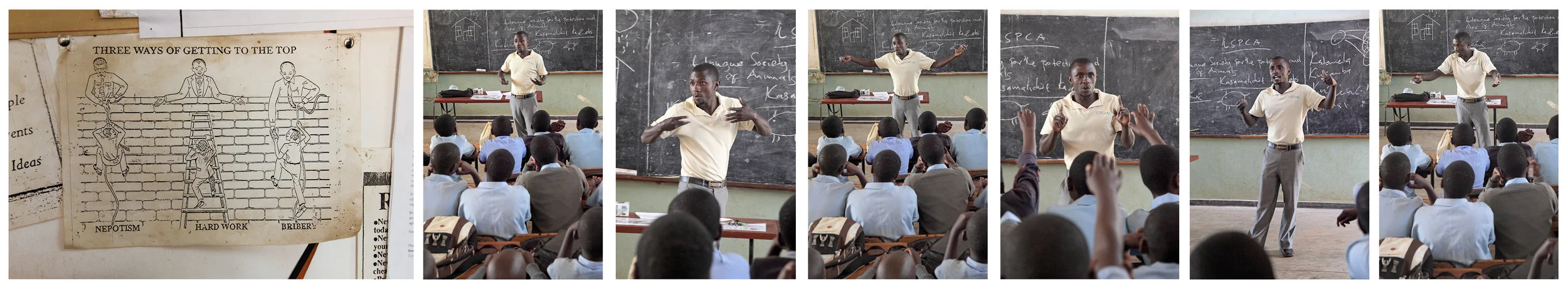

Most of the animal welfare issues in Malawi are attributed to a general lack of awareness rather than individual acts of deliberate cruelty. In response to this, the LSPCA has fashioned an education programme targeting state schools that on the whole are less likely to receive any form of information referencing animal care. Children aged between 10 and 12 are perceived to be the most responsive and therefore the most capable of changing their behaviour, not only now but also into the future. The sessions address the issues of basic care, disease control, rabies vaccination, nutrition and shelter. They are designed to be as interactive as possible involving not only the pupils but the resident teachers as well.

Joseph enters the classroom as I attempt to discretely place myself amongst the children, of whom there are easily over a hundred. The room is quite cool, the darkness pierced by sharp beams of light forcing their way in through small open brick windows. Joseph begins calmly and politely, slowly building in pace and passion as the lesson progresses. He is a confident and powerful speaker. Its almost religious and I feel that I could be in a church. The pupils are absorbed, almost falling over each other to grab his attention in order to answer his summarising questions. And then, after an hour, its over. We leave to enlightened applause. Not such a reserved personality after all.

The afternoon is spent in the company of Victoria Gavey, a 24-year-old vet from the island of Jersey. She is a month into her 6-month contract, but projects the appearance of having been here for years. She is responding to a request from a local farmer, Ackim Mwale, who owns over 650 chickens (quite a major concern) who aren’t laying as often as they should be. Victoria assesses the conditions, records the details of the situation and discusses various opportunities where the welfare of the birds can be improved, which should hopefully result in the desired increase in egg production. The farmer appears content with the visit and we depart in order to beat the setting sun. The power cuts roll over into a second night.

Tuesday morning is, unsurprisingly, dry and hot. I’m on my way to Area 25C (the city is divided into districts known as Areas) to document one of the LSPCA’s mobile spay and neuter clinics. Lilongwe has seen a marked increase in its stray dog population and an increase in the incidence of rabies. In response to this, the LSPCA has established a concerted programme for its mobile clinics, making them free and deliberately locating them in the capital’s poorest communities.

I arrive just as Dr Richard Ssuna and Joseph (who is today performing the role of veterinary assistant) are carrying their equipment into a red brick building of unfinished construction. Permission to practice here has been granted by the local elder or chief (in this instance a woman called Saka) who is sitting proudly by the entrance surrounded by local inhabitants and dogs of all conditions. It’s the first time that the LSPCA has visited this area and it looks like it’s going to be a busy day.

Dr Ssuna stands between the two metal tables that are to be his operating platforms for the day. Originally from Uganda and a post-graduate of the Royal Veterinary College in London, he has been the LSPCA’s Project Manager and Chief Veterinarian since February of 2009. Softly spoken, with a warm and thoughtful demeanour, he calmly prepares his implements. Outside Joseph is compiling an orderly list of mostly canine patients.

The work is hard, intense, hot and dusty. In one corner of the building, there are animals being prepared for surgery. In the middle are the two operating tables themselves, constantly occupied. In another area, there are those animals that are gently recovering from surgery. Owners and vets constantly criss-cross each other as the morning quickly slips into the afternoon. As the local schools begin to close for the day, more and more children are drawn to the area and start mingling with the adults. Intrigue and curiosity build until inch by inch and one by one, all begin to gradually encroach through the doorway and into building. Eyes young and old witness the final treatments, transforming the room into a true operating theatre.

As the clinic is dismantled and loaded into the back of the pick-up, menacing black clouds gather above as the orange-red earth is blown up around us. The rainy season is a good month over the horizon, but it sends a sharp notice of its inevitable arrival as the day concludes.

Wednesday morning begins overcast and damp, but the rising sun vanquishes any residual moisture. I’m travelling with Joseph and the RSPCA International’s Donnamarie O’Connell and today’s destination is Likuni, a small dusty town to the south-west of the capital, which is the focus of the LSPCA’s Backyard Chicken Project. The aims of the programme cover topics such as husbandry, breeding and basic nutrition, but it also places a great emphasis on combating the problem of the fatal Newcastle disease, for which a simple vaccination can be given. Chickens are owned by an estimated 95% of Malawian households, providing not only an important source of food but also of income, so this project not only addresses animal welfare but tackles poverty as well.

The roads vanish as we enter Likuni’s clusters of crumbling red-brick buildings. We are on our way to meet a Mr Senza, a well-respected elder in the district of Mtsiliza, who has co-ordinated one of the vaccination programmes. The main aim of the day is to collect information from those directly involved in the project to determine the effectiveness of the programme and to build on its successes. We arrive to be greeted by a proud and eloquent man who immediately welcomes us into his home. Soon he and Donnamarie are warming updating each other on the local progress before we have to move on to visit the plethora of people in the vicinity who are actively involved in the scheme.

The journey culminates with a visit to the local vaccinator, a woman called Chifundo Mwase. The vaccinators, like the co-ordinators, undergo practical training from the LSPCA (in partnership with the government) so that the local communities can organise the project themselves, albeit with external expertise and funding. Chifundo has clearly heard of our presence in the area for as we arrive, she has donned a pristine LSPCA t-shirt. She is not the only one waiting, as a large crowd of local children have also gathered around her house. As Donnamarie and Joseph gather the information that they need, I entertain the children by taking their portraits and showing them their images on my camera. The same said children joyfully follow us out of the district until we bounce and bump out of sight. My final night consists of an ironic mixture of power cuts interrupted by lightning.

Thursday morning is dry and hot. I have to be at the airport by midday, so I’ve just enough time to visit the clinic, take some final portraits, give my thanks and say my goodbyes. It has only been a brief visit, but long enough to be affected by the professionalism and determination of all of those who work and volunteer at the LSPCA. In Malawi, animals are not luxuries but integral to the communities they live in, providing security, food or income. Veterinary care and knowledge of animal welfare in the country is almost non-existent, making the work of this charity not only incredible, but also invaluable to all those it touches.

All Imagery and Words - Copyright Joseph Murphy/RSPCA